Japan’s agricultural policy towards food security improvement. Key strategies, initiatives and outcomes

Based on the Global Food Security Index (which takes into account the issues of food affordability, availability, quality and natural resources resilience), Japan is considered to be 6th most self-sufficient country in the world. However, the Japanese government still sees the national food security issue as problematic for the country’s stability due to heavy dependency on agricultural import.

To overcome the trend, Japan utilizes multiple mechanisms to eventually improve agricultural self-sufficiency. The main focus is kept on the following 4 critical levers – i) productivity improvement, ii) agricultural employment improvement, iii) demand shift towards traditional dietary and new markets opening and iv) SDG agenda. The research also provides a case study of technologies implemented in the agricultural field in Japan in order to improve the self-sufficiency level. Moreover, emphasis is made on the government policies to develop the local market and to build the new markets abroad for the domestic farmers’ production expansion.

Introduction

Internationally Japan is considered to be a country with a high level of food security and widespread access to quality nutrition as per Global Food Security Index (GFSI) accepted at the International Food Summit back in 1996. The Index takes food availability, affordability, quality and safety, natural resources resilience into consideration. In 2022 Japan ranked #6 globally, improving from #8 in 2021 and #11 in 2012 [Global Food Security Index 2022, 2023]. However, the Japanese government sees a serious challenge in the sphere of food security due to a low production self-sufficiency index which has been declining over recent decades. Until as late as the 1980s, when the quarters on some import products were imposed, Japan had suffered from low level of food self-sufficiency [Markarian, 2017, p. 49]. Calories-based self-sufficiency index (how much calories from the daily diet is produced inside the country) was just 37% in 2018, having declined since 1961, when it had been 78% (fig. 1). According to this factor, Japan ranks one of the worst in the world and can not ensure independence from agricultural import, like, for example, the US or Australia (excluded from the chart due to visual limitation – average index 230 and growing).

Figure 1. Self-sufficiency index by country, calories based.

Overview of the agricultural industry

There are several critical factors that affect the negative dynamic in agricultural industry. The first and foremost self-sufficiency reduction is related to the change in consumption structure. If in 1961, most of the food consumption remained traditional for the Japanese dietary customs, including mostly rice [Assmann, 2017, p. 121], over the stated period it has changed dramatically (fig. 2).

Figure 2. Change in food consumption habits in Japan (1961–2019).

The share of rice has dropped from about 50% to just 22% while the importance of fats and oils, meat, and milk products has significantly grown. The growing demand in these segments, which have never been a core part of the Japanese diet, can not be fulfilled solely by the domestic agriculture due to the peculiarities of the lands and soils, geographical location of the country and other factors. Taking this into consideration, the country can hardly become self-sufficient in the current environment with the existing consumption pattern (fig. 3).

Figure 3. Self-sufficiency of Japan by product.

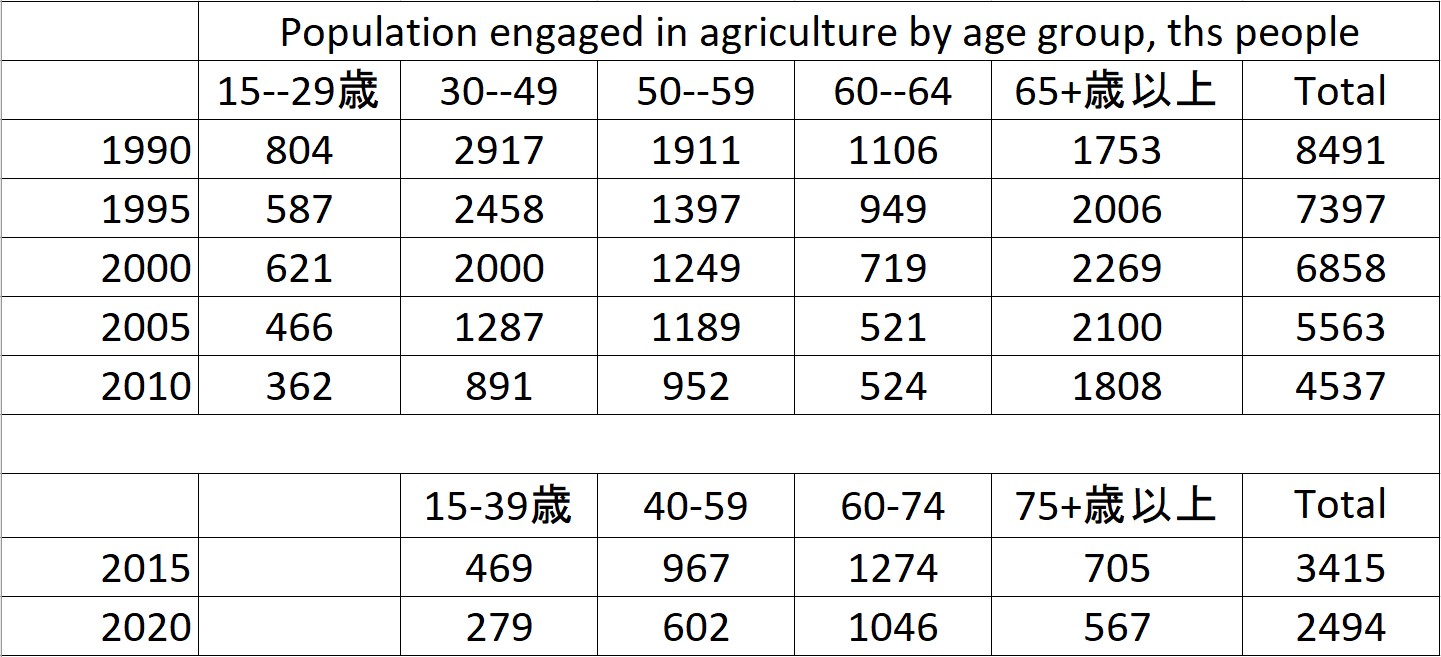

In addition, the country faces reduction of the population in general as well as its aging, which has a direct impact on agriculture. The total number of people involved in agriculture has decreased by almost 4 times over the past 30 years. Mainly the older population works in agriculture, with a very fast reduction of the younger generation involved. In 1990, the share of people younger than 49 years old was approximately 44%, but it has reduced to 28% in 2010 (fig. 4). In the modern period, the Japanese government has even reconsidered borders of age groups for statistics. The share of younger generation continues to plummet (from 14% of

Figure 4. Population engaged in agriculture by age group (thousands).

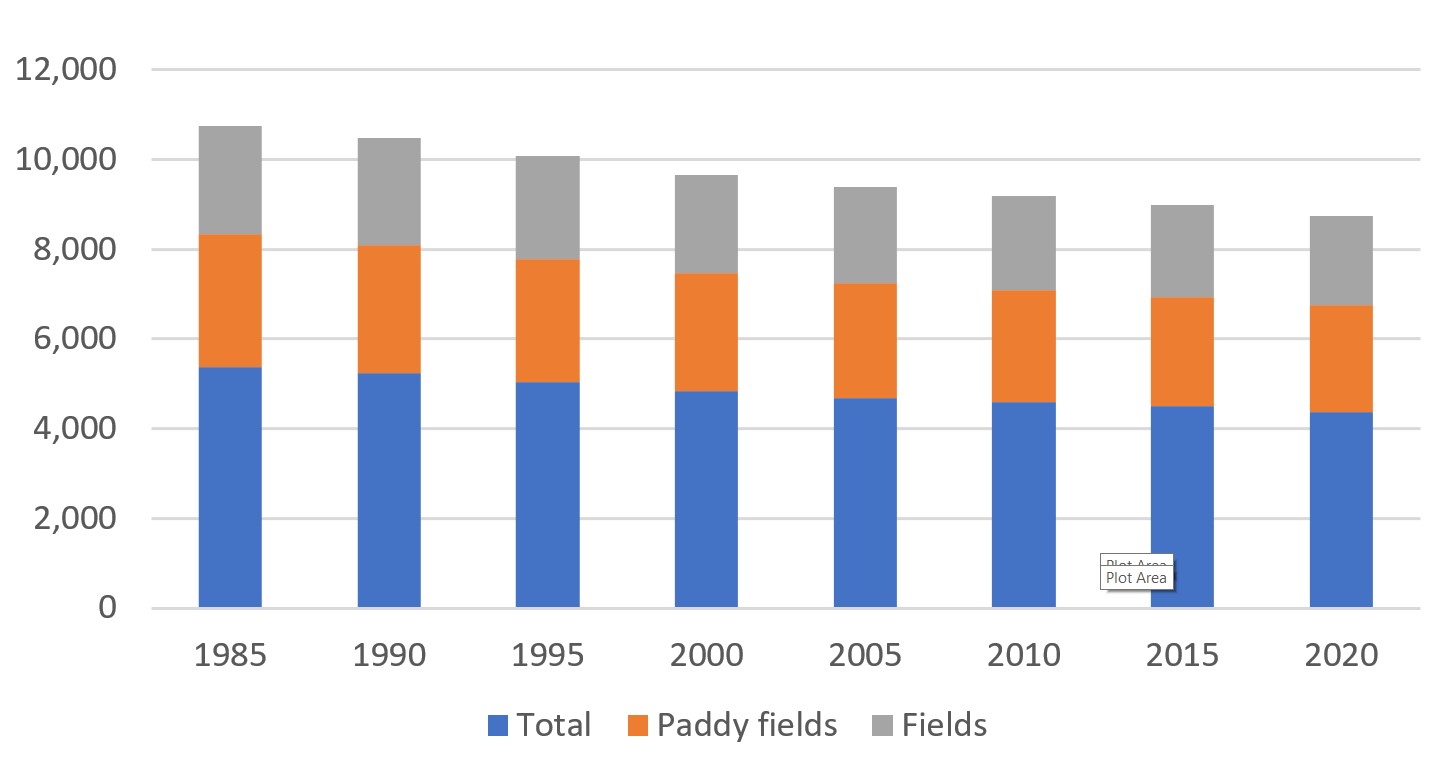

Another affecting trend is contraction of the cultivated land itself. This can be linked to a decrease in the number of farmers, partly due to the Fukushima nuclear accident that resulted in the nuclear contamination of the soil in Japan and a decline in the quality of the soil itself (fig. 5), which requires decent amount of fertilizers and is difficult to cultivate.

Figure 5. Area of cultivated land (thousands hectares).

The total area of cultivated land in 1985 was approximately 5.4 million ha. By 2000, it has decreased to 4.8 million ha, and today it is just 4.4 million ha. In 2014, only 12% of the land in Japan was arable [Nihon tokei nenkan, 2022]. For a country with deep roots in agriculture, which has managed to provide self-sufficiency for a long period of its history, it is a heavy hit. Though the share of agriculture in the GDP is approximately 1% of the total economy (5.6 billion yen in agriculture out of 562 trillion yen total GDP in 2021), it is still highly important for the national stability and security [Nihon tokei nenkan, 2022].

Last but not least, the government realizes the challenge of long-term sustainability of the agriculture sector in the country. This is related to soil sustainability and waste management.

Most soils in Japan are difficult to use – about 31% of Japan is Andosols, 38% is Cambisols (mostly located in the north of the country) and 13% is Fluvisols. Andosols and Fluvisols are rich with minerals and microelements, however, they are difficult for agriculture in the long term. Andosols are rapidly losing minerals and not replenishing easily, thus, they cannot be used every year without fertilizers. Fluvisols are located in the areas with a high risk of flooding, which is challenging to predict especially in a country like Japan. These soils are widely used for agriculture around the world, though they are more difficult to cultivate outside of Tropic and Subtropic areas which is the case for Japan [Oguchi, 2021, p. 27]. The government recognizes that these peculiarities of Japanese soils are a long-term challenge to the land sustainability.

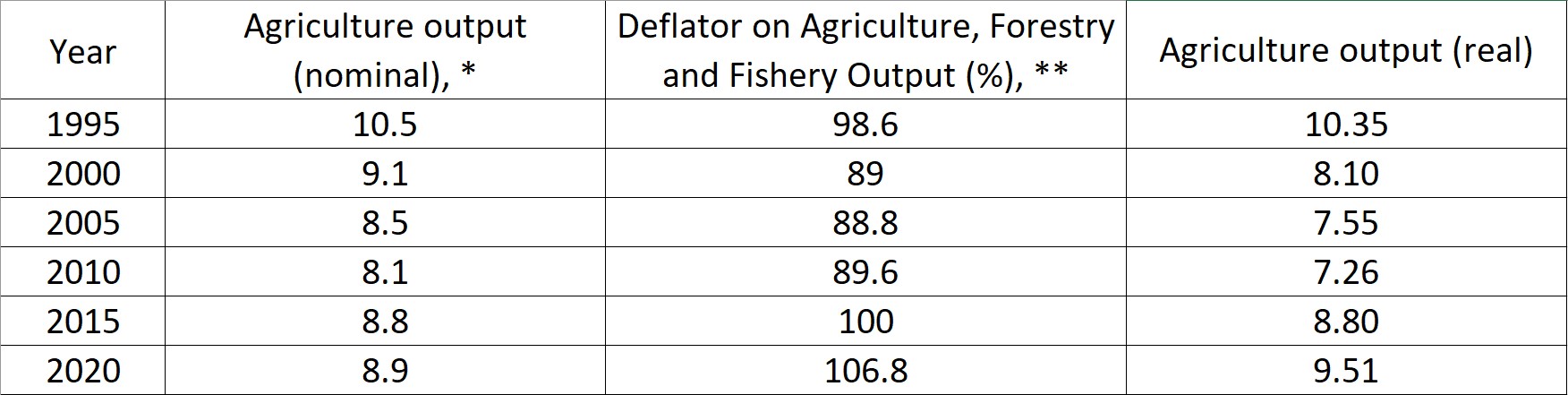

In the last years, after making note of all critical agricultural challenges, the government has made solid progress in reverting negative agriculture output trends. The total agriculture output had been steadily reducing from 1990 to 2010, but since then it has started to grow (fig. 6). The agricultural data used in the graph is provided by the Statistics Bureau of Japan, estimated in nominal prices. If we recalculate the data into real values, applying the deflator provided by the Cabinet Office of the National Account of Japan (fig. 7), the described tendency will be reinforced.

Figure 6. Agriculture output and productivity.

Figure 7. Agriculture output in real and nominal terms (trillion yen, benchmark year - 2015). *Japan Statistical Yearbook 2023. Statistics Japan. **Cabinet Office. National accounts for 2021.

Another important conclusion coming out of the graph data is a significant increase of agricultural productivity in the country. The output has soared from approximately 1.3 billion yen/1000 people in 2000 up to 3.6 billion yen/1000 people in 2020, while the number of people employed in agriculture dropped from 6.9 million in 2000 to 2.5 million in 2020. Productivity per hectare has also slightly improved but did not show equally impressive results [Nihon tokei nenkan, 2022].

For a long period of time the food self-sufficiency ratio has been steadily becoming worse. Statistics show a significant decrease of the ratio on calorie supply basis. This ratio reached 38% in 2019, which is 12% lower than it had been in 1994 and 45% lower than in 1965. Production value basis has also decreased and reached 66% in 2019, which is 12% and 20% lower than the figures in 1994 and 1965 respectively.

The figures indicate that self-sufficiency ratio has somewhat stagnated in the period between 1999 and 2004. The total agricultural output has come back to growth since 2015, though it had been declining since its peak in 1984 (fig. 8). The production income of agriculture is also growing, reaching 3.8 trillion yen in 2017, the highest since 2004, and remained at the amount of 3.5 trillion yen in 2018 (fig. 9).

Figure 8. Total agricultural output (trillion yen). [Summary of the Annual Report on Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas in Japan, 2021, p. 19]

Figure 9. Agricultural production income (trillion yen). [Summary of the Annual Report on Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas in Japan, 2021, p. 19]

The domestic food industry production value has also been back to growing curve (fig. 10). In 2019 it increased by 1.0 trillion yen in comparison with the previous year in all categories: eating/beverage services, relevant distribution industry, food manufacturing industry, achieving 101.5 trillion yen (fig. 10).

Figure 10. Domestic production value of food industry (trillion yen). [Summary of the Annual Report on Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas in Japan, 2021, p. 12]

The export value of agriculture, forestry and fishery products has been increasing for the last eight years (fig. 11). Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, it continued to grow. In 2019 it reached 912.1 billion yen and in 2020 – 921.7 billion yen (the value of exports, including small value cargo, etc., was even higher in 2020 at 986.0 billion yen). However, the target amount of 1 trillion yen, posed by the government, was not achieved [Shokuryo nogyo noson kihon keikaku, 2020].

Figure 11. Export value of agricultural, forestry and fishery products and foods (billion yen). [Summary of the Annual Report on Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas in Japan, 2021, p. 13]

Slight fluctuations have been observed in the last 3 years, which can be explained by the impact of COVID-19. Statistics showed the decrease of the agricultural output in 2019 by 1.8% in comparison to the year before, dropping down to 8.9 trillion yen. In the same period, agricultural production income decreased by 4.8%, dropping to 3.3 trillion yen. The main reason for this change was the total output decrease and specifically lower prices for hen eggs and vegetables.

The core part of the agriculture transformation is centralized government support of the industry since it requires transitional resources. It is interesting to note that it is not the first case in Japanese history when the government took the leading role in the society transformation. The Japanese government practiced the same in Meiji era, when the country made the transition from the agrarian system of economy to the industrial one.

Nowadays, the efforts are becoming even more vigorous, as the outbreak of the new COVID-19 disease made it clear that even well-organized supply chains can be blocked at once and ruin the import flow of food from abroad. In such conditions, the problem of food supply security becomes even more important.

Human resources issue

Japan faces severe issues with the drop of the number of people involved in agriculture (fig. 12). If in 1990 there were 8.5 million people involved, the number has dropped almost 3.5 times in just 30 years. At the same time, the drop in land use is quite significant as well, and the trend is continuing.

Figure 12. Change in agricultural labor and land use, 1961 to 2019. [United States Department for Agriculture (USDA) Economic Research Service – processed by Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/agricultural-labor-land?country=AUS~USA~JPN~FRA]

Compared to the US or Australia, the decrease is dramatic. Australia and the US also face a decrease in agricultural labor, but the drop is not that significant – only by 30% and 50% respectively.

Due to population aging and decreasing number of farmers, the Japanese government promotes policies aimed at the increase of the rural areas’ attractiveness. In March 2021 a new Long-Term Plan of Land Improvement for the period from FY2021 to FY2025 was published. It includes i) the transformation of agriculture into a growth industry by strengthening the production infrastructure, ii) promotion of rural areas where diverse groups of people can continue to live, iii) strengthening the resilience of agriculture and rural areas.

The government realizes the challenge and pressure and focuses on reversing the trend from 2 angles.

Firstly, the aim is to bring more people into the fields. To reach the goal, the government actively supports the “return to the countryside” (田園回帰) phenomenon, trying to spread the attractiveness of rural areas nationwide and help to re-evaluate the possibility to combine agriculture and other jobs. In Japan today one can find a so-called “half-farming and half-X” movement that contributes to regional revitalization, popularizing new lifestyles such as dual life (living in two areas) and satellite offices (二地域居住).

One of the tools used is the “New Agricultural Personnel Fair” (introduced in 2000 for those who wished to start farming) supported by Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF). In 2020, comprehensive counseling sessions “Agriculture EXPO” have been launched, organized by local public organizations, agricultural colleges, agricultural lawyers and the “Agricultural Employment and Change of Job LIVE” organization, specialized in the employment of agricultural lawyers. The number of visitors to the event is increasing, indicating that urban residents are becoming more involved in the topic. However, all these activities do not bring visible results.

Another way to address the problem of insufficient human resources is improving the productivity level by implementing digital technologies such as robots, AI, and IoT. New technologies cover all aspects of agriculture including agricultural sites operations as well as back-office processes like administration and logistics.

The digital transformation is stimulated by the government and strongly supported by business. The first step towards smart agriculture development was made in 2013, when the MAFF established a “Study Group for Smart Agriculture Promotion”. It boosted the momentum for the parties concerned, and the Cabinet Office's Strategic Innovation Promotion Program and other public-government collaborations received a boost, although the active phase of the initiative started in 2019.

In 2020, the MAFF set the following target in the Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas Basic Act: “In order to improve productivity and make agriculture a growth industry while responding to the problem of aging among farmers and labor shortages in the future, we will introduce digital technologies to meet consumer needs through the data-driven agricultural management” [Shokuryo nogyo noson kihon keikaku, 2020] The Agriculture Digital Transformation was abbreviated as Agriculture DX in the document. It was also planned that almost all farmers in Japan would practice digital technologies by 2025 [Nogyo no dejitaru toransufomeshon, 2021].

The development of new approaches and technologies is provided on the base of the “Program for Promotion of On-Site Implementation of New Agricultural Technology” [Nogyo shingijutsu, 2019], which was approved in June 2019. The program covers the following fields:

Image of agricultural management in the future

The state of advanced agricultural management that is expected to be implemented by the introduction of new technology is shown in detail for each farming type (paddy field, cropland, open-field vegetables, greenhouse agriculture, flowering, tea, fruit tree gardens, livestock)

Roadmaps for each technology

The roadmaps to 2025 are provided for new technologies in 6 categories: drone-related technology, robot-related technology, environment control technology, livestock, production, and business management.

Measures to promote implementation of technologies

Another step is the announcement of the “Smart Agriculture Promotion Comprehensive Package” [Sumato nogyo, 2020], which is supposed to promote collaboration between government institutions in order to accelerate the smart agriculture development in Japan.

To implement the data-driven agriculture, the Special Service eMAFF was established by MAFF. The Service promotes the digital transformation of agriculture, forestry, and fisheries by bringing administrative procedures online. It also provides subsidies and grants for the projects connected with the digitalization of agricultural management.

One of the important programs of the package is the “Service Education Program for Smart Agriculture Support”. It was approved in October 2020. The program provides information on successful smart practices in various spheres of agriculture (sowing, pest control, and harvesting), agricultural machine provision, temporary staff search and hiring, data analysis.

One more useful instrument is an agricultural data linkage platform called WAGRI [Norinsuisansho, 2021]. It had started to operate in April 2019 and by the end of September 2021, 61 private businesses were using the service. The application allows to display all the data necessary for analysis. It helps to manage the appropriate work period much more effectively.

Due to the reduction of the number of workers in logistic services, it is important to develop unified standard logistics systems and equipment storage robot facilities, which can help to achieve operational efficiency and increase labor savings. In logistics, information technologies such as electronic tags (RFID) and truck reservation system are being introduced. The important part of the efforts is aimed at the increase of railroad carriage share, reducing truck delivery. The switch from manual labor to mechanization and introduction of robots, AI, and IoT systems is welcome on all stages of the production and delivery chain.

Various improvements of the agricultural production infrastructure were introduced in 2019, including implementation of smart agriculture that uses automated machinery, information and communications technology in water management, etc. There was an effort to consolidate rice paddies into larger partitions of 50 ha and more, which reached 11% in 2019. At the same time, culvert drainage was installed on 46% of the paddy fields, which upgraded them to multipurpose paddy fields. 24% of upland fields were covered by irrigation facilities.

The following cases can be good examples of the projects that became successful due to the implementation of new technologies [Nogyo no dejitaru toransufomeshon, 2021]:

Kalm Kakuyama Co., Ltd. (Hokkaido)

A large-scale dairy farm achieved labor savings introducing a large number of milking robots and efficient feeding management.

Kalm Co., Ltd. was organized in 2014 by a cooperative of five dairy farmers of smaller size. The target was to improve work efficiency and reduce production costs using the economy of scale. In 2015, the company started to use a free stall barn and eight automatic milking robots. This change made the farm to be number one in Asia. Then the company introduced equipment for controlling diseases and reproduction by linking with milking robots and analyzing the components of raw milk from each cow. Now the farm owns more than a thousand cows.

Yokota Farm (Ibaraki Prefecture)

The company developed low-cost production by performing field management using IT systems.

In 2008, the production started from a 16 ha land plot and has been expanding rapidly in the recent years, growing to about 150 ha. Efficiency of the cultivation was achieved by introducing an automatic water supply system, which is operated by a distant field management system or even smartphone. Rice is planted and harvested with the use of a transplanter and combine system. Today the company is testing two drones, which are designed to spray chemicals with a distant navigation control system. The new technologies reduced the costs significantly, now they are about a half of the national average.

OPTiM Corporation

The company entered the market in 2015. It provides farmers with e-management and planning solutions to improve the quality of produce, overall productivity, and reduce the costs by utilizing robots, AI, and IoT. It also provides outsource drone operators who can make field images, analyze them and decide whether it is necessary to apply pesticides. The company also purchases all the crops produced by the clients registered in the system.

Vivid Garden Inc.

The company introduced an e-management platform which helps to sell products directly to individual consumers and restaurants.

The “Eating Chok” e-management platform is a service provided nationwide for companies in agriculture, forestry and fishery that meet certain cultivation standards. It provides an opportunity to sell products online and deliver them directly to individual consumers and restaurants. The platform accumulates feedback and preferences of the consumers and analyzes the data. It is expected that the results will help the producers to plan their future production.

Smart agriculture is designed and promoted within the framework of the Society 5.0 national strategy development. It provides beneficial results, improving the agricultural productivity in general. The output remains sustainable despite the reduction in labor.

Building new markets for the farmers

The government also supports farmers by stimulating demand on the domestic market through reorientation to Japanese traditional food and increase in the export of profitable agricultural products.

Measures to redirect domestic food consumption towards locally produced products

To accelerate the measures for local agriculture development, “The Headquarters on Creating Dynamism through Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries and Local Communities”, headed by the Prime Minister, was created in May 2013. The purpose of the organization is to devise special measures for agriculture in order to make it a source of vitality for Japan in the future and promote the sustainable development ideas.

The government provides special mechanisms to encourage Japanese consumers and food-related businesses to select domestic agriculture. In addition, it takes measures to preserve the food culture to pass it on to the next generations. Steps are taken to educate the population, from children to adults, such as promotion of “Japanese-style eating habits”, understanding of the importance of agriculture and rural areas that support the functions of the ecosystem as a whole, rural nature and taste experience promotion.

One of the most important goals is to make producers and consumers closer to each other, including both logistics and cultural aspects. Initiatives to tighten up the community are being widely spread. New marketing solutions are being developed, which are targeted at making producers and consumers closer to each other.

The idea to shift the culture towards harmony with the environment is considered to be implemented via deeper understanding of the efforts and ingenuity of agriculture, forestry and fishery companies and food business operators. It is expected that all these efforts will encourage the domestic consumers to choose simple locally produced food. The event that supported the policy happened in December 2013, when “Washoku” (和食) – traditional dietary Japanese culture – was added to UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity [Washoku, 2023]. The MAFF provides mass media support of local agricultural production. For instance, the “TASOGARE” program was launched on the Ministry’s official YouTube channel “BUZZ” to educate the audience on consumption issues and promote local agriculture.

The MAFF is starting a new national project, called “Thinking about Japan from Food. Food Shift in Japan”. The main idea is to deepen the connection between food producers and consumers. It is stated that thinking about food is thinking about the future society and the quality of everyday life. The background of the new approach is the implementation of the Society 5.0 strategy, which was announced in 2017 by the Cabinet of Ministers as the basic policy for the investment strategy for the future development of the country. The goal is to create connected industries, which will take into consideration the society’s needs and solve social problems. The main idea is to change the mindset of producers from “things” to “value” production.

Solid efforts are put to ensure consumption of agricultural and forestry products within the region where they were produced. To implement the idea, the network of direct sales offices, operating within the regions, is being developed. The formation of agricultural cooperatives is getting promoted. For the first time the concept was reflected in the MAFF document “Basic Policy for the Integration of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries and Related Businesses by Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery Companies, and Promotion of the Use of Local Agricultural, Forestry and Fishery Products” in 2011.

To support the initiative, the School Food Procurement Act 1954 gives priority to the locally produced agricultural products, but the results are still low. The goal was to increase the income of agricultural products direct sales offices with annual sales of 100 million yen or more by 50% by 2020. However, in 2019 the increase reached only 25.9%.

Regarding the non-tariff measures, Japan introduced the Japanese Agricultural Standard (JAS), developed by the MAFF, which became a legal requirement. JAS covers not only agricultural products, but wood products as well. The last related document “Regulation for Enforcement of the Act on Japanese Agricultural Standards” was published in February 2021. The document focuses on the importance of quick and up-to-time response to changes in the consumers’ diversifying needs and their choice rationalization.

Measures to achieve export expansion

To overcome the Japanese market limitation for export growth, the Japanese government made strong focus on the industry. On April 1, 2021, the Prime Minister Suga announced that “expanding export of agricultural products is the key to raising local income and creating vibrant regions” [Norin suisanbutsu, 2021]. The MAFF set the following target for the industry to develop – the export volume has to increase to 5 trillion yen by 2030 (1.4 trillion yen for agricultural products, 0.2 trillion yen for forest products, 1.2 trillion yen for marine products, 2.0 trillion yen for processed foods, excluding small cargo export about 200 thousand yen or less) [Shokuryo nogyo noson kihon keikaku, 2020]. It means that the export volume should increase approximately twice within 5 years, in comparison with 2020 (922.3 billion yen) [2020 nen no norin suisanbutsu, 2021].

A significant shift to the export promotion strategy, provided by the Japanese government, happened in the second half of the 2010s, when “The Headquarters on Creating Dynamism through Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries and Local Communities” was created, headed by the Prime Minister. The purpose of the organization is development of special measures for agriculture development in order to make it a source of vitality for Japan in the future and promotion of the ideas of sustainable development.

The consultations organized by the Headquarters abolished some limits on the export. For example, 39 countries, out of the 54 that introduced import restrictions in the wake of the TEPCO Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power station accident, have removed their measures. One more important result was that a range of countries or regions (USA, Macao, Thailand, Saudi Arabia, Australia, EU, Singapore) decided to reduce the ban on Japanese export or relax quarantine requirements in 2020 [Shokuryo nogyo noson no doko, 2021].

In 2019 the MAFF issued Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Products and Food Export Promotion Act (Act No. 57). It created the legal basis to establish one-stop export support office for exporters, called “Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries Products and Food Export Headquarters”, which was opened in April 2020. The office develops the export strategy, provides export information for the companies, issues export certificates, strategically responds to the process of formulating international standards and standards of export destination countries, approves and registers facilities for exports. It also develops an annual action plan for export facility approvals and registrations and market access negotiation schedules with foreign governments.

“The Strategy for Export Expansion of Agricultural, Forestry, Fishery and Food Products” has been issued in 2020 by “The Headquarters on Creating Dynamism through Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries and Local Communities” [Nōrinsui sangyō chiiki, 2020]. The strategy lists the exact measures to support export-oriented local agriculture producers and to help them to meet the foreign demand. It is aimed at achieving the goal set earlier by the MAAF for the export growth.

The export promotion measures, developed by the government, can be divided into three groups [Shokuryo nogyo noson no doko, 2021].

Set specific targets for each product item that maximizes Japan's export strengths

There is a wide variety of exported Japanese products. However, the value of each category of export is quite small, because the export is mainly a “surplus of the domestic market”, and the market-in approach export has not been established in Japanese practice yet. It is considered to be a weak point of Japan, which limits the opportunities to compete on the international markets.

27 priority export product categories were listed to overcome the limitations. [Shokuryo nogyo noson no doko, 2021] These are the items considered to be highly valued overseas, and the government is ready to provide multilateral support for the export increase of these products.

In addition, in April 2021, a number of special production zones focused on export were identified (1227 areas). The list of target countries/ regions was created as well taking into consideration the export market trends and environment, and a set of export targets was developed for each country / region.

The collaboration between the Japanese side participants (production, distribution, and export businesses) is being organized and supported by the government. The government also takes the lead over collecting information on export markets and developing sales strategies. In cooperation with such public organizations as JETRO and private research companies, the export potential researches are provided, based on the market size, infrastructure, food orientation, etc. [Shokuryo nogyo noson no doko, 2021].

Support domestic agriculture businesses ready to export applying the idea of market-in approach

The government provides priority support to the businesses aiming to export which includes environmental enhancements. In April 2021 “A Bill to Revise the Act on Special Measures Concerning the Facilitation of Investment in Agricultural Corporations” has been submitted to the National Diet of Japan in order to support investors into the export businesses. The government has also encouraged development and investments into the high quality and efficient export logistical chain, which includes storage facilities, port and airports.

Overcome barriers by “transcending ministries and agencies’ boundaries and working together as one government”

The government is determined to bring together a unified control center. The “Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries Products and Food Export Headquarters” will take charge in organizing an “Export and International Bureau” in the MAFF that will be in charge of implementation of the export strategy.

The government will also support advancement and certification of HACCP facilities that follow foreign regulations. Additional measures will also be implemented to regulate the outflow of IP to enhance the protection of Japan.

As a result of the government’s actions during the last decade, Japan's export of agricultural, forestry, fishery and food products have more than doubled. [Nōrinsui sangyō chiiki, 2020]. Even under the conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic it continued to grow. In 2019 it reached 912.1 billion yen and in 2020 – 921.7 billion yen (the value of exports, including small value cargo, etc., was even higher in 2020 at 986.0 billion yen). But the goal of 1 trillion yen, posed by the government, has yet not been fully achieved [Shokuryo nogyo noson kihon keikaku, 2020].

Conclusions

Agriculture takes up merely about 1% of GDP in Japan, although structurally and strategically it is a very important part of the economy, strongly supported by the Japanese government, that tries to at least maintain it at the same GDP levels. It is also important to transfer the agriculture to the new level of technologies to keep the sector in the mainstream of digitalization process.

The government views food security as one of the major problems for the national development of agriculture. Challenging soils combined with the aging population and continuous urbanization of the nation, as well as other factors like shift in the national consumption behavior or land nuclear contamination due to Fukushima, resulted in low levels of food security (possibility to produce sufficient amount of food for the nation locally), becoming a threat for the nation. This threat have become even more formidable in the recent years when a perfect storm of the COVID-19 pandemic, combined with the blockage of the Suez channel and increased goods turnover between China and the US, led to a massive increase in the transportation cost, insufficiency of containers and incapability of blue color workers to drive the operations, resulting in both massive delays of the international freight and increase of its cost.

The government had noticed the issue even before the described events and initiated a series of measures to improve the situation in agriculture, focusing on the following directions:

- stimulating agriculture growth by increasing the demand for locally produced food, promoting traditional Japanese dietary values and building Japanese food markets abroad;

- productivity improvement by using new technologies, IoT, logistics improvement and others;

- promotion of de-urbanization and focus on the new way of doing agriculture (i.e. urban agriculture or combined office workers/farmers approach) to revert the decrease of agriculture-related workers;

- drive sustainability agenda in agriculture to reduce harm for the nature, ensure long-term sustainability of the lands, and decrease food waste.

The reforms that have been promoted in recent years in Japan showed mixed results. On one hand, it is evident that the Japanese government’s pursuit to shift the institutional platform of the Japanese society towards the sustainable growth is strong. Agriculture is not an exclusion. The efforts of the government institutions have sufficiently increased over the last decade. There is a range of success cases, like the growth of new farms being run by young people, which are aligned with the new requirements. The tendency is also supported by the COVID-19 circumstances, as some urban human resources moved to rural areas and started to contribute to regional revitalization. On the other hand, in the agriculture-related industry, the results are still quite poor. Most of the posed goals have not been achieved yet.

Though the government makes efforts to develop the agricultural sector and tries to be optimistic in its prognoses and plans, most of the variables are still becoming worse. The food security level is declining, and the intellectualization process is going on slowly: the transition to robots, AI, and IoT systems in the agricultural sector and related industries remains mainly on the paper.

While both farms and farmland are in decline, efforts are being made to prevent a large drop in domestic production as new technologies promising more efficient production are gradually introduced. Though in general, we should finally conclude that the real target of the Japanese government is not to increase the food security index, but at least to maintain the declining share of domestic food supply at the present level, using the new technologies.

In general, the variables in agriculture have been declining during decades. Recently, when the government realized the critical tendency and started to devise measures to change the trend, the situation has at least stabilized. In most of product categories, except rice, the production volume is growing, that can be explained both by the domestic and foreign demand increase.

The combination of fiscal measures and technology stimulation in agricultural industry are accepted well in Japan. The productivity of the sector per worker increased almost 3 times from 2000 till 2020. However, the number of commercial households is declining, negatively affecting the total results of the providing policy.

![Figure 8. Total agricultural output (trillion yen). [Summary of the Annual Report on Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas in Japan, 2021, p. 19] Figure 8. Total agricultural output (trillion yen). [Summary of the Annual Report on Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas in Japan, 2021, p. 19]](https://api.selcdn.ru/v1/SEL_83924/images/publication_images/107163/8-1.jpg)

![Figure 9. Agricultural production income (trillion yen). [Summary of the Annual Report on Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas in Japan, 2021, p. 19] Figure 9. Agricultural production income (trillion yen). [Summary of the Annual Report on Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas in Japan, 2021, p. 19]](https://api.selcdn.ru/v1/SEL_83924/images/publication_images/107163/9-1.jpg)

![Figure 10. Domestic production value of food industry (trillion yen). [Summary of the Annual Report on Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas in Japan, 2021, p. 12] Figure 10. Domestic production value of food industry (trillion yen). [Summary of the Annual Report on Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas in Japan, 2021, p. 12]](https://api.selcdn.ru/v1/SEL_83924/images/publication_images/107163/10-1.jpg)

![Figure 11. Export value of agricultural, forestry and fishery products and foods (billion yen). [Summary of the Annual Report on Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas in Japan, 2021, p. 13] Figure 11. Export value of agricultural, forestry and fishery products and foods (billion yen). [Summary of the Annual Report on Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas in Japan, 2021, p. 13]](https://api.selcdn.ru/v1/SEL_83924/images/publication_images/107163/11-1.jpg)

![Figure 12. Change in agricultural labor and land use, 1961 to 2019. [United States Department for Agriculture (USDA) Economic Research Service – processed by Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/agricultural-labor-land?country=AUS~USA~JPN~FRA] Figure 12. Change in agricultural labor and land use, 1961 to 2019. [United States Department for Agriculture (USDA) Economic Research Service – processed by Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/agricultural-labor-land?country=AUS~USA~JPN~FRA]](https://api.selcdn.ru/v1/SEL_83924/images/publication_images/107163/image12.png)