Regional language politics in Kazakhstan in terms of Turkestan region

In June 2023, following an open online discussion, the “Concept of Language Policy Development in the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2023–2029” was adopted, which outlines, among other objectives, the “Main Directions for the Transition to Latin Script” [Concept of Development, Chapter 2, Paragraph 2, 2023], indicating the government's advancing plans in this regard. On October 19, 2023, this Concept was approved [Kazakhstan Approves the Concept, 2023], and by 2029, the following key outcomes are expected as a result of its implementation: 1. The proportion of the Kazakh-speaking population in the republic – 84%; 2. The proportion of the population speaking three languages – 32%; 3. The proportion of the population enrolled in courses on the new alphabet and spelling rules – 15%; 4. The proportion of documentation by central state and local executive bodies conducted in the state language – 94%; 5. The proportion of the terminology fund based on the spelling rules of the Kazakh language's Latin alphabet (cumulative) – 40% [Concept of Development, Chapter 6, 2023].

It is evident that among the objectives of the program’s implementation, no languages other than Kazakh are mentioned (one can infer those one of the three languages referred to in the program is Russian, alongside Kazakh and English). Furthermore, of the five objectives, two specifically address the new Latin alphabet. Prior to this, for 30 years after independence, Kazakhstan pursued a flexible and soft language politics, which proclaimed a gradual expansion of the scope of application of the Kazakh language, but retained the possibility of comfortable use of Russian, Uzbek, Uyghur and Tajik languages. It is evident that the direction of language policy has now shifted.

The presence in the country of two large linguistic communities (in Kazakh and Russian) brings the situation in Kazakhstan, closer to the situation in many regions around the world where such communities emerged as a result of the disintegration of larger states, sometimes in a colonial context. This primarily pertains to the post-Soviet states that share historical and cultural conditions similar to those of Kazakhstan over the past 100 years. It also applies to countries like Canada and Singapore, which were formed at different times as a result of the dissolution of the British Empire.

Researches have more frequently focused on the linguistic situation in the post-Soviet Baltic states, where the influence of a significant Russian-speaking minority on the processes of establishing a new national identity has been examined. Some researchers viewed the existence of a large number of Russian speakers as a potential threat for conflicts or even the formation of a new post-Soviet ideology. This perspective was articulated by Inesse Ozolina in her article “Language Use and Intercultural Communication in Latvia” [Ozolina, 1999, p. 11–12] and by Cemile Asker, who compared the situation in Kazakhstan and Estonia. In both cases, the authors advocated for the existence of only one (state) language, which they considered to be the titular language [Asker, 2014, p. 76–77].

Other researchers argue that a multifaceted [Cheskin, Kachyevski, 2019, p. 15] language policy is more justified in Kazakhstan, as it allows for the preservation of the linguistic and ethnic identity of the titular population while also avoiding the alienation of minorities, particularly the significant Russian-speaking population in Kazakhstan [Reagan, 2019, p. 467]. Official bilingualism and multilingualism are also supported in Canada and Singapore, which have developed in a post-colonial context rather than a post-Soviet one. In Canada the language politics is aimed at supporting two official languages English and French [Action Plan, Pillar 3, 2023 ], in Singapore, along with 3 local languages, English, the language of the former metropolis, has been approved as the official language [Kuo, 1983, p. 2; Dixon, 2005, p. 625–626].

At the same time researchers have noted that in Kazakhstan the number of schools with non-Kazakh language of instruction gradually decreased [Fierman, 2006, p. 102–106; Savin, 2019, p. 96–101] against the backdrop of decline in the Russian-speaking population of Kazakhstan and the increasing role of Kazakh as a symbol of nation-building after the Soviet period, which was declared colonial. However, there have not yet been any studies dedicated to the analyzing the language policy of Kazakhstan after 2019 focused on the situation in single region.

Some authors have repeatedly noted the importance of taking into account regional specifics when analyzing language politics and language planning in Kazakhstan. In particular, A. Zhikeyeva, believing that “differences in the linguistic situation of individual regions: north and south, border regions are generally recognized”, admits that many aspects of the regional consideration of language politics remain out of the field of view of researchers. In her opinion, “the peculiarity of the linguistic situation of northern Kazakhstan lies in the presence of a Kazakh-Russian bilingualism of a special kind, namely, the predominance of Russian language among the entire population as the language of interethnic communication”. In this regard, the researcher believes, “there is an urgent need for a regional approach in studying the language situation in the Republic of Kazakhstan” [Zhikeyeva, 2014, p. 3].

Meanwhile, Turkestan region is not only one of the most densely populated in the country, but also the most dynamic in terms of population growth. Since the goal of any language policy is to promote internal unity and sustainable development of the country, the purpose of this article is to study the specifics of the language situation and language policy in the Turkestan region in the context of opportunities and challenges during the implementation of the set goals in Concept of Language Policy Development in the Republic of Kazakhstan fоr 2023–2029.

To achieve this goal, the following tasks need to be accomplished:

1. Study the overall picture of the ethnolinguistic situation in the Turkestan region through the lens of official statistics and materials from state and public institutions responsible for language development and ethnocultural diversity.

2. Identify the perception of the current language situation and language policy among different categories of residents in the region and their readiness to achieve the goals set forth in the Concept of Language Policy Development.

3. Determine the areas of the language situation and language policy activities that appear most problematic and least effective in the eyes of the local population, and prepare recommendations for central and regional authorities responsible for implementing language policy that could assist to effective intercultural communication between ethnic communities and authorities.

Since the authors have many years of experience conducting similar studies in the region [Junusbayev et al., 2017], this experience was utilized in preparing the research activities for the present study. To ensure a comprehensive examination of the language situation in the region, methodological approaches from various disciplines were employed.

1.The ethno-demographic situation was studied using the several methods: of analyzing current statistical materials and data from the 2021 National Census. Additionally, the method of interpretation of statistics of education departments, documents of authorized authorities in the field of language politics in various districts of the region was applied. In particular, we studied the ethnic composition of individual settlements, the language of instruction in schools located in these settlements, reports on the activities of language development departments in different districts and villages, instructions from local authorities for educational and cultural institutions on the implementation of language politics and introduction of Latin alphabet. The period from 2022 to 2024 was covered.

2. Public opinion was studied through a population survey. A total of 1000 respondents were surveyed, predominantly young individuals, as they are expected to become the primary participants in the future activities of the Language Policy Development Concept. The questionnaires were proportionally distributed according to a representative sample based on gender and ethnicity among urban and rural areas of the region.

As it has been already noted, in October 2023, the “Concept of Language Policy Development in the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2023–2029” was adopted [Concept of Development, 2023]. The objectives of this concept were markedly different from the language planning tasks proclaimed in the Message of the President K.-J. Tokayev to the people of Kazakhstan, along with the thesis that “the role of Kazakh language as the state language will be strengthened and the time will come when it will become the language of interethnic communication”, there are assurances to continue creating “conditions for development of languages and cultures of all ethnic groups in our country” [Message of the Head of the state Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, 2019]. Thus, marking the changes associated with increased attention to the tasks of modernizing Kazakh language and expanding its dissemination, the Concept contains very few mentions of development of other languages of Kazakhstan.

This is directly stated in the text of the Program itself, where, with reference to the data of “Public Opinion” research institute, it is stated that in 2018 the share of the population who speaks the state language was 85.9%, and the share of the population who speaks Russian was 92.3% [State Program, 2020]. Specifying the features of the current situation, the authors of the Program note that “at present, the following language competencies exist in Kazakhstan: Kazakh-speaking; Kazakh-Russian bilingualism; Russian-speaking; ethnic-Kazakh, ethnic-Russian bilingualism or ethnic-Russian-Kazakh trilingualism; Kazakh-Russian-English trilingualism”. At the same time, “the predominance of Russian-Kazakh bilingualism in the linguistic environment” is fixed as a problem (in the same place). Therefore, it is not accidental that there has been increased attention in recent years to the expansion of the Kazakh language.

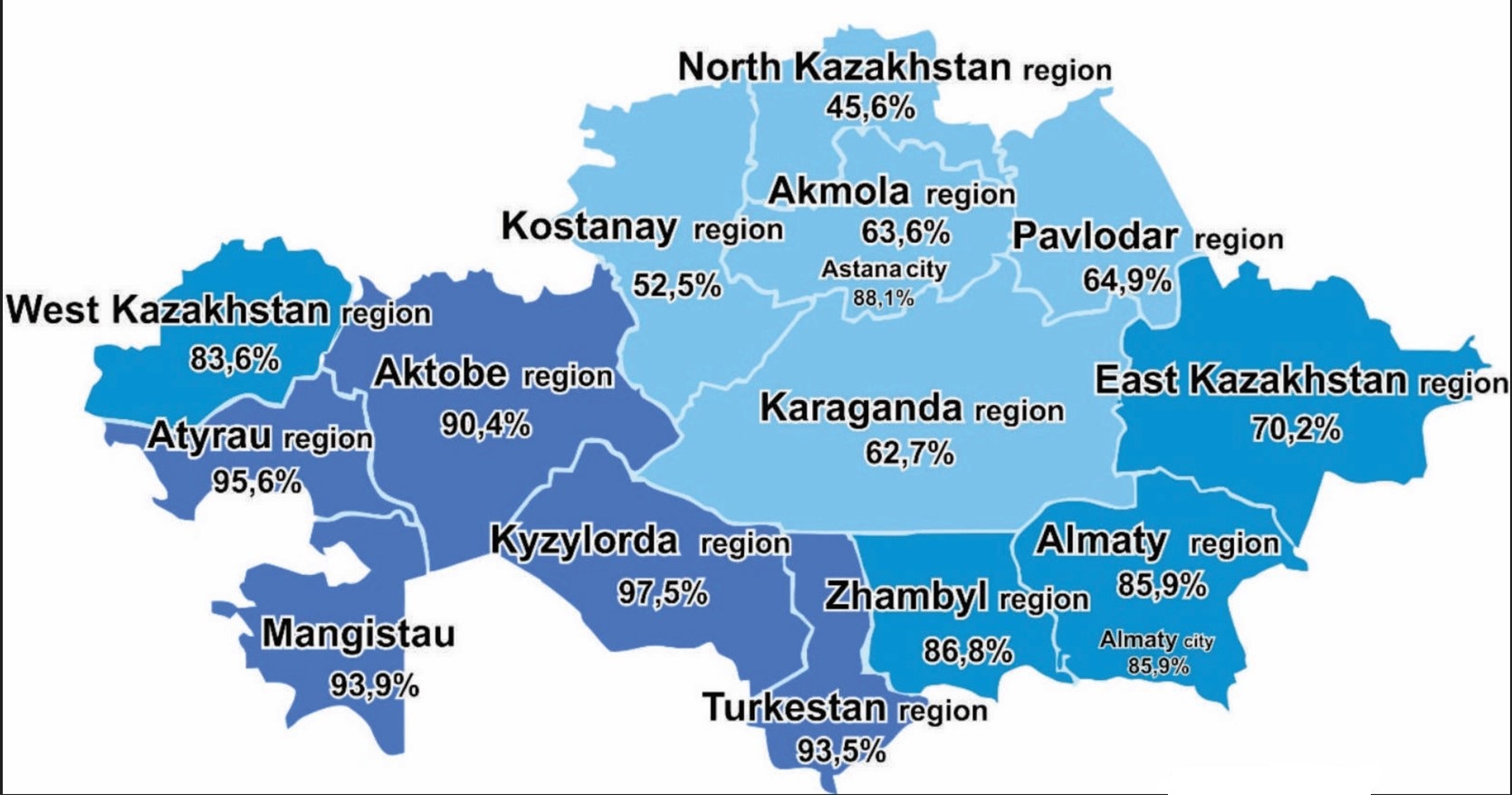

Fig. 1. Share of citizens who speak the state language by the regions of Kazakhstan. Source: Made by the authors on the base of National Population Census 2021.

Considering the distribution of the ratio of the proportion of those who speak and do not speak Kazakh language in the composition of the population of various regions of the country (See Table 1), it is easy to conclude that the patterns of the spread of language competencies depend on regional specifics. It is obvious that in the regions where, according to the 2021 census, the share of those who speak Kazakh language was more than 90% (Aktobe, Atyrau, Kyzylorda, Mangistau, Turkestan regions), completely different language competencies will dominate than in those areas where this indicator was 45–60% (Akmola, Karaganda, Kostanay, Pavlodar, North Kazakhstan) (fig. 1). Moreover, not only language situations will differ, but also regional language politics strategies that take into account the needs and demands of speakers of different languages in a particular region.

Table 1. Number and share of citizens who speak and do not speak the state language by regions of Kazakhstan

| speak state language | do not speak | speak state language | do not speak | |

| Kazakhstan | 13 768 408 | 3 426 306 | 80.08 | 19.9 |

| Akmola region | 459 730 | 263 559 | 63.6 | 36.4 |

| Aktobe region | 727 039 | 77 576 | 90.4 | 9.6 |

| Almaty region | 1 651 365 | 268 856 | 85.9 | 14.1 |

| Atyrau region | 56 3591 | 26 119 | 95.6 | 4.4 |

| West Kazakhstan region | 507 363 | 1026 85 | 83.2 | 16.8 |

| Zhambyl region | 925 551 | 140 579 | 86.8 | 13.2 |

| Karaganda region | 774 693 | 460 468 | 62.7 | 37.3 |

| Kostanay region | 407 727 | 368 342 | 52.5 | 47.5 |

| Kyzylorda region | 697 560 | 18 122 | 97.5 | 2.5 |

| Mangistau region | 593 942 | 38 524 | 93.9 | 6.1 |

| Pavlodar region | 453 789 | 244 739 | 64.9 | 35.1 |

| North Kazakhstan region | 231 096 | 275 607 | 45.6 | 54.4 |

| Turkestan region | 1 682 673 | 117 084 | 93.5 | 6.5 |

| East Kazakhstan region | 866 860 | 367 268 | 70.2 | 29.8 |

| Astana city | 965 975 | 130 325 | 88.1 | 11.9 |

| Almaty city | 1 424 551 | 392 337 | 78.4 | 21.6 |

It is clear that in regions where Kazakh language proficiency is at around 50% of the total population, entirely different pedagogical staff and methods for teaching Kazakh are needed, especially in the absence of a stable Kazakh-speaking environment.

The Turkestan region provides us with a unique example of a situation where dominant Kazakh language teachers could help students learning in schools that do not use Kazakh as the language of instruction. Let us examine how this is implemented in practice.

For today, the language situation in Turkestan region reflects the specifics of the ethnic composition of the population, which is dominated by Kazakhs (75% of all residents of the region) and 93% of the population speaks Kazakh language. Accordingly, the lion’s share of the document flow is carried out in Kazakh language, education in 742 out of 1000 schools in the region is conducted only in Kazakh language. Teaching in Russian is conducted in 8 schools and in Uzbek in 1 school. In the remaining 249 schools, education is conducted in two languages, more often in Kazakh/Uzbek and Kazakh/Russian, but in 12 schools in Kazakh/Tajik. At the same time, several zones can be distinguished in the region, which differ according to the share of the Kazakh population, the prevalence of Kazakh language in schooling and everyday speech behavior.

Table 2. Number and share of the largest ethnic communities in the population of cities and districts of Turkestan region as of 1 January 2023

| Kazakhs | Uzbeks | Tajiks | Russians | |||||

| Turkestan region | 1 595 151 | 75.2 | 378 463 | 17.8 | 38672 | 1.8 | 29 443 | 1.4 |

| Turkestan city | 145 641 | 66.2 | 68 340 | 31.1 | 1 603 | 0.7 | ||

| Arys city | 75 323 | 95.3 | 1 610 | 2.0 | ||||

| Kentau city | 67 155 | 67.5 | 25 881 | 26.1 | 2 996 | 3.0 | ||

| Baidibek district | 46 867 | 95.8 | ||||||

| Zhetysay district | 167 760 | 89.5 | 2 566 | 1.4 | 12 528 | 6.7 | 1 479 | 0.7 |

| Keles district | 122 830 | 91.8 | 7 337 | 5.5 | ||||

| Kazygurt district | 107 469 | 92.4 | 7 130 | 6.2 | ||||

| Maktaaral district | 89 942 | 69.6 | 12 003 | 9.3 | 15 430 | 11.9 | 1 916 | 1.5 |

| Ordabasy district | 121 485 | 95.1 | 1 093 | 0.9 | ||||

| Otrar district | 50 699 | 98.2 | ||||||

| Sairam district | 63 708 | 27.5 | 152 851 | 65.9 | 3 822 | 1.6 | ||

| Saryagash district | 188 604 | 86.1 | 7 201 | 3.2 | 9 278 | 4.2 | 2001 | 0.9 |

| Sauran district | 41 446 | 41.4 | 57.1 | |||||

| Suzak district | 57 168 | 90.1 | 4 741 | 7.5 | ||||

| Tolebi district | 83 050 | 68.7 | 22 331 | 18.4 | 5 285 | 4.4 | ||

| Tyulkubas district | 85 179 | 80.1 | 8 347 | 7.8 | 3 920 | 3.7 | ||

| Shardara district | 80 825 | 95.6 | 1 177 | 1.4 | ||||

| Shymkent | 845 228 | 70.9 | 189 271 | 15.8 | 1 399 | 0.1 | 75 186 | 6.3 |

Source: Made by the authors on the base of current statistic of Turkestan region.

Firstly, these are areas where the share of the Kazakh population reaches from 89 to 98% of all residents and the only language of instruction in most schools, everyday, industrial communication, document flow is the state language. These are Baidibek, Zhetysay, Keles, Kazygurt, Ordabasy, Otrar, Suzak, Shardara districts and Arys city. A small number of schools with Uzbek language of instruction exist only in Zhetysay (1), Keles (1), Kazygurt (4) districts and in Zhetysay district there are 3 schools with Tajik language of instruction.

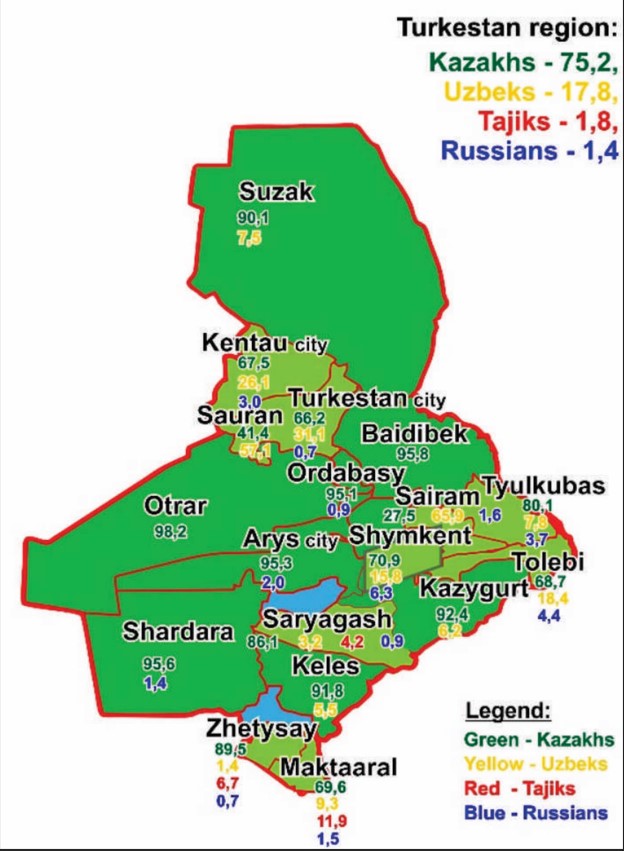

Fig. 2. Percentage of ethnic communities in population of cities and districts of Turkestan region as of 1 January 2023. Source: Made by the authors on the base of Current statistic of Turkestan region

Secondly, these are areas in which the share of the Kazakh population is from 68 to 86%, with the dominance of Kazakh in some sectors of the language sphere, other languages are publicly used: Russian, Uzbek, Tajik. These include Maktaaral, Saryagash, Tolebi, Tyulkubas regions (fig. 2). In Maktaaral region there are three schools with Uzbek language of instruction and 5 schools where, along with Kazakh language, Tajik language is also used in the learning process. In Saryagash district, there are 1 Uzbek-language school, 4 Tajik-language schools and 7 Russian-language schools. In Tolebi district, 5 schools teach in Uzbek language, in Tyulkubas district – in 1.

Finally, there are areas where the share of Kazakhs in the total population ranges from 27 to 66% and where, with the widespread use of Kazakh language, the role of Uzbek language used is somewhat more noticeable, which inevitably makes adjustments to the implementation of language politics in these local micro-regions. These are Turkestan and Kentau cities, Sairam and Sauran districts, where most of the schools with Uzbek language of instruction in the region are located: from 42 in Sairam district and 19 in Sauran district to 11 in Turkestan city and 6 in Kentau city.

In Shymkent city, the share of Kazakhs is 70.9% of the total population, out of 245 city schools, only one (non-state) school does not teach in Kazakh language – classes are conducted there in Russian. In 91 schools, only Kazakh language is used in the learning process, in 117 – Kazakh and Russian languages, in 22 schools – Kazakh, Russian and Uzbek languages, in 14 – Kazakh and Uzbek languages2.

Thus, in about 26% of schools in Turkestan region and 62% in Shymkent city, teaching takes place in languages other than Kazakh. Of 249 thousand students in the city’s schools in 2023, 172 thousand students (68.9%) studied in Kazakh language, 58 thousand students (23.4%) in Russian and 19 thousand students (7.7%) in Uzbek. This implies the existence and maintenance of an appropriate infrastructure: training and advanced training of teachers working in different languages in the course of the educational process, publishing textbooks in the relevant languages, including methodologists in the staff of education departments of some cities and districts who supervise teachers working in Russian, Uzbek and Tajik languages.

In addition, the sociodemographic situation in Turkestan region can be considered as a model for the development of the language situation in Kazakhstan as a whole in the medium term: it is characterized by a reduction in the Russian-speaking population and an expansion of the representation of the Uzbek and Tajik population, which will be typical for some other regions of Kazakhstan in the coming decades.

In most districts of the region, the language of document circulation of state institutions, citizens’ appeals, public events, court hearings, etc. is Kazakh language. Russian language is more often used in Shymkent city, Sairam, Tolebi and Zhetysay districts in the course of everyday communication, including among employees of state and educational organizations.

Analyzing the situation in the Turkestan region in light of the goals of the Concept of Language Policy Development for 2023–2029, the following observations can be made:

1. The dominance of teachers working in Kazakh could enable achieving a level of Kazakh language proficiency significantly above 84%, making this goal quite achievable.

2. The goal of having 32% of people proficient in three languages (Kazakh, English, and Russian) appears doubtful, as regular teaching in Russian occurs only in some cities of the region, and Russian language instruction is at an adequate level. English language education and the use of English in teaching at schools or universities involve no more than 2–3% of students.

3. Training courses for mastering the new alphabet for 15% of the population would be feasible with significant increases in funding and the establishment of such courses in every educational institution. The prerequisites for this were established in 2019, but as of 2024, these centers are not operational.

4. Achieving 94% document circulation in Kazakh is quite attainable; it only requires creating the necessary conditions in schools where instruction is not conducted in Kazakh.

5. There are currently no grounds to expect an increase in the terminological fund to 40%, as there is still very little literature using the Latin alphabet available in schools and universities.

PERCEPTIONS OF THE PROSPECTS FOR IMPLEMENTING THE CONCEPT OF LANGUAGE POLICY DEVELOPMENT FOR 2023–2029 AMONG RESIDENTS OF THE REGION BASED ON POPULATION SURVEYS

Most of 1000 respondents were aged between 18 and 45, which reflects the particular relevance of language policy initiatives for younger individuals who will experience the effects of transitioning the Kazakh language to the Latin script over the coming decades. For this reason, the sample was intentionally skewed in terms of education and employment: over 65% had higher education, and more than 75% were students or employees, as they are likely to be active consumers of language products for an extended period, making their perspectives particularly valuable for the research.

The ethnic composition of respondents mirrored the ethno-demographic proportions of the Turkestan region's population: 70% were Kazakhs, 13% Russians, 9% Uzbeks, with the remaining respondents being Tatars, Tajiks, Azerbaijanis, Koreans, and Germans. Based on similar considerations, the majority of respondents were surveyed in urban areas, where visual information using various languages and graphic symbols is more prevalent and influential on the overall social situation.

In response to the question, “What language do you speak at home?” the majority of respondents expectedly chose Kazakh (64.6%), indicating that only a small portion of the Kazakh population speaks a different language at home. At work, 56.4% speak Kazakh, and in the public sphere, 64%. These data suggest that Kazakh is the primary means of communication for the younger segment of society and is slightly less in demand in professional settings.

However, almost 50% of respondents noted that they sometimes feel discomfort due to insufficient knowledge of a particular language (Kazakh, Russian, Uzbek, English, etc.). This suggests an insufficient level of multilingualism development in society. Nevertheless, only about 10% of respondents frequently encounter such situations, indicating that this issue likely does not significantly affect the nature of language communication. Nonetheless, this is a significant indicator whose prevalence needs to be clarified through group discussions.

The majority of respondents (74.7%) would like their children to speak Kazakh, while 23.7 % prefer Russian. Predictably, more than 65,6% of respondents consider teaching their children Kazakh as the most important, 22,5% prioritize English, and 24,8% prioritize Russian (respondents could choose several answers). As we can see, the survey results confirm the correctness of the chosen direction of language policy aimed at promoting trilingualism in society, as these three languages are considered the most important for learning by the respondents. Additionally, 68% of respondents would prefer that documents in state and public institutions be in Kazakh, with only 17% choosing Russian. Among rural residents, the preference for the Kazakh language in different spheres of life is more pronounced.

The relevance of the data based on respondents’ answers is confirmed by statistics from the language development departments, which indicate a sustained demand for studying Russian. This is evidenced by the stable number of classes with Russian as the language of instruction and the slow but steady increase in the number of people studying Russian in language centers.

Respondents' opinions varied significantly on the question, “Do you support the transition of the Kazakh language to the Latin script?” 19% and 26% respectively support it “completely” and “mostly”, while 32% and 22% “rather do not support” and “do not support at all”. Similarly, the distribution of responses to the question, “How important do you consider the transition to the Latin script for the country's development?” was mixed: 27% consider this transition “very important,” 44% “not very important,” and 25% “not important at all.”

Assessments of the efforts of local authorities and public institutions in the Turkestan region regarding the development of the state language, as perceived by respondents, are as follows: 18% of respondents are aware of such activities and have participated in them, 36.4% have heard of them, and 43.8% have not heard of such activities. A similar picture is observed regarding activities for the development of other languages in the region: 20% are aware, 34% have heard something, and 44.9% have not heard at all. However, the efforts to promote the transition to the Latin script are even less known: 15% are aware, 35% have heard something, and 49.7% have not heard at all.

The results of the mass survey show that the absolute majority of respondents consider the dominance of the Kazakh language in public, communicative, and educational spheres as natural for the region and are oriented towards self-realization in such a situation. Nevertheless, some respondents regularly experience discomfort due to a lack of knowledge of a particular language, indicating the insufficient development of real multilingualism in all spheres of social life, which requires further study.

The preference for the Kazakh language does not imply the exclusion of other languages from use, as the demand for proficiency in these languages persists. This primarily concerns English and Russian, as well as the languages of the communities compactly residing in the region: Uzbek and Tajik.

A smaller portion of respondents consider the transition to the Latin script important for the country and are ready for it compared to those who think otherwise. The primary argument for the “transition to the Latin script,” according to the study participants, is the “modernization of the Kazakh language,” which aligns with the main thesis of the government narrative on this matter. This circumstance creates an opportunity for a gradual shift in the position of the majority of respondents, provided that a gradual and unobtrusive explanatory effort is made, highlighting the advantages of using the Latin script for different categories of citizens.

Based on the research results, the readiness of state institutions and the population to implement the tasks set can be assessed as follows in the Concept of Language Policy Development in the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2023–2029:

– Primarily, this involves understanding the leading role of the Kazakh language in forming the linguistic environment in the region, which indicates the feasibility of the set goal – 84% of the population speaking Kazakh.

– There are challenges in achieving the trilingualism level of 32%, which requires additional local efforts;

– There are conditions that may support achieving the goal of 15% of individuals completing specialized courses on the use of the Latin alphabet; however, this goal is not guaranteed by the current level of interest.

– A majority of respondents expressed their readiness to use documents and official materials in the Kazakh language in their daily lives;

– Viewing the transition to the Latin script for the Kazakh language as a process to be implemented over many years, with the parallel use of the Kazakh language in Cyrillic in the public and educational spheres during the initial years of the reform. This calls into question the possibility of achieving a 40% expansion of the terminological corpus using the Latin alphabet.

Key Identified Shortcomings and Recommendations for Their Improvement:

1. The low effectiveness of teaching Kazakh to non-native speakers is primarily attributed, in our view, to the use of outdated methods centered around rote memorization of specific phrases and poems, and repetitive learning of dialogues disconnected from contemporary life circumstances. This issue affects both children in schools and adults in language centers. The practice of language teaching needs to more effectively incorporate new digital technologies that vividly and accessibly demonstrate the benefits of mastering Kazakh. It is also necessary to increase the number of centers for adult education in Kazakh, Russian, and English, and to raise teachers' salaries. Currently, the number of attendees is minimal, and the annual expansion rate of 1–2% is clearly insufficient to overcome the linguistic discomfort still prevalent in the region.

2. The relatively low level of readiness among the region's residents for the transition to the Latin script for the Kazakh language in the near future can be partially explained by the lack of extensive public discussions outside a narrow expert community. Events dedicated to language policy for the general public are usually conducted using arguments applicable to the entire country. However, there is a demand for discussions on the advantages and disadvantages of the Latin script from the perspective of the everyday needs of various categories of the population and individual citizens, rather than society as a whole. Implementing such open discussions requires additional efforts but would significantly increase the level of acceptance of the reform within society. It may be necessary to utilize the experience of education development departments in certain districts of the Turkestan region both regionally and nationally: introducing specialized consultants for the implementation of the Latin alphabet who would train school and language center teachers, similar to the existing consultants for Kazakh, Russian, Uzbek, and Tajik languages.

***

The findings of the study indicate that regional specificity is crucial both for the implementation of current language policy and for achieving the goals of the Concept of Language Policy Development for 2023–2029. No other region in Kazakhstan has such a high concentration of ethnic communities or such a diverse range of schools, cultural institutions, and media in different languages. This allows for the identification of gaps in the new concept that need to be addressed to maintain multilingualism, facilitate intercultural communication, and strengthen internal societal cohesion as a condition for sustainable development. Furthermore, the experience of operating multilingual state and public institutions in the region will enhance the effectiveness of addressing new tasks, such as the implementation of the Latin alphabet, across the country. From a theoretical perspective, the study demonstrates that even 30 years after gaining independence, multilingualism traditions continue to support internal stability within society, contrary to some assumptions in the literature suggesting that multilingualism would hinder the development of national identity in the country.